BINNEKRING BLOG

Light art at AfrikaBurn: Finding our sublime selves?

This is a summary of a paper presented at the 14th National Conference of the South African Journal of Art History, hosted virtually by Nelson Mandela University in September 2020.

By John Steele,

Walter Sisulu University; [email protected]

AfrikaBurn 2019 (Photo: Jonx Pillemer)

Despite being off the grid, each night at AfrikaBurn is awash in the spellbinding ephemerality of light art, from throbbing horizon to throbbing horizon. My focus on light art for this paper is mainly enabled by reflecting on aspects of four works created by Robert van der Vliet between 2011 and 2018 at AfrikaBurn, who I hereby thank for responding comprehensively by email and in an interview to questions posed during the difficult early days of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown 2020.

In 2011 Robert’s first light art work at AfrikaBurn, Olmec Head, was set up next to the Binnekring Road in such a way that the eyes appeared to follow passersby from back or front, both day and night. The Olmec Head was illuminated from below at night so as to create what is known as a hollow face optical illusion. This is a trick achieved by lighting the empty interior of the artwork in such a way that the face and nose appear to visually be normal and are seen as convex even though that side of the artwork is concave.

Olmec Head, 2011, 2 meters high x 1.8 meters wide. Robert van der Vliet is seen here soon after the artwork was set alight (Photos: Adriaan Wessels)

In Find Yourself (2012) he focused on producing optical illusion by projecting laser lumia light onto a 10-metre-tall four sided obelisk from four peripheral towers. Robert explains that the title Find Yourself partly refers to an intention to provide a large glowing obelisk as a beacon that would help people navigate the Binnekring and encampments at night, as well as being an encouragement to participants to use AfrikaBurn as an opportunity for personal discovery.

Find Yourself, 2012, 10 meters high x 12 meters square footprint, multi-media including laser electronica (Photo: Scott J Brooks)

In Find Yourself the illusion involves creating a sense of flowing light by focusing projected beams from each of the eight self-made laser diodes shining through respective home-made lumia wheels of moving stippled glass, the direction of lumia wheel movement making the resulting light seem to be rising or falling.

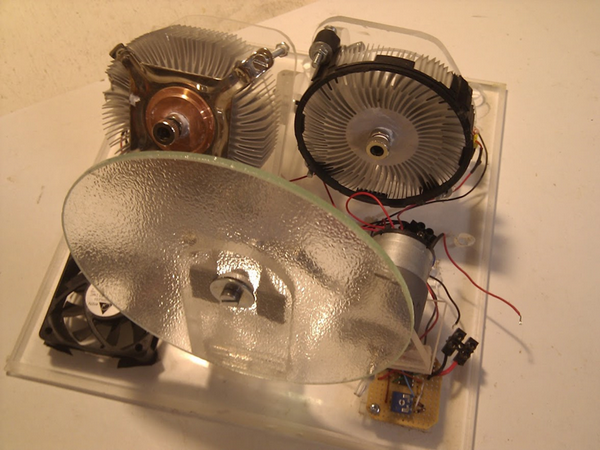

Detail of one of the Find Yourself projectors showing the 15rpm 12v gear motor to rotate the lumia wheel disk, which can be seen in the front (Photo: Robert van der Vliet)

The particular trick Robert applied in Find Yourself is to shine each pointed laser beam through a line lens so that it spreads into an upright vertical line, which once projected from a tower makes it look, from close-up, as if it is rising in flame-like licks of light, yet from afar at night in the Binnekring it looks as if the obelisk is made of glass, filled with water, and has air bubbling up.

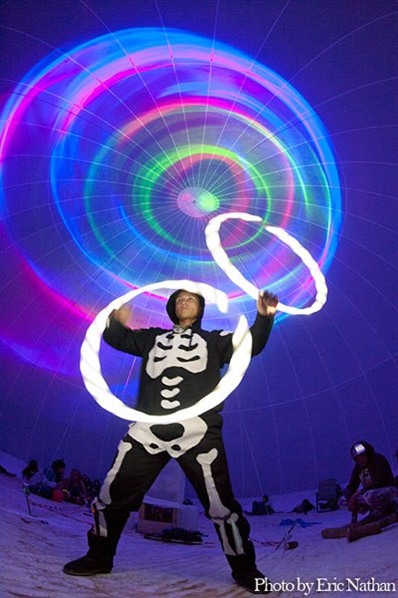

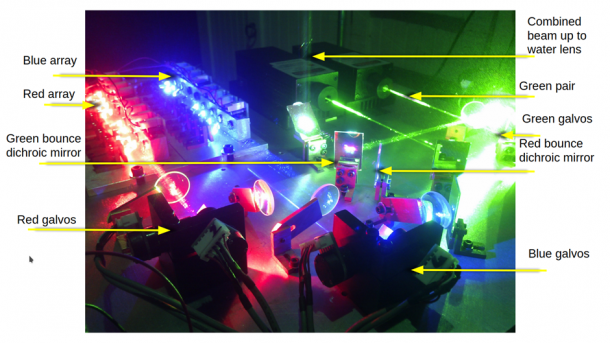

In 2013 Robert engaged with an entirely new light art adventure Aurora, that featured almost impossibly complex self-designed and constructed arrangements of enhanced red, blue and green laser lights projected through water onto the inner surface of a perfectly hemispherical screen. Ingeniously designed, this dome is air supported, held up purely by positive air pressure, controlled at the entry and exit by a revolving door air lock.

Aurora, 2013, 15 meters diameter x 7.5 meters high, multimedia including laser projection and associated electronica (Photo: Eric Nathan)

Impetus for this work arose out of a curiosity about how to make a machine that would look inside illuminated water wave and ripple patterns and project what it saw in such a way that these patterns could be seen from inside as well as outside the screen. Put another way, Robert has explained in an email that he “sought to make a non-deterministic/analogue machine in response to the deterministic/digital machines we see so much of the time”.

Inside Aurora, 2013. Performer is Shaheen van der Schyff (Photos: Eric Nathan).

Robert met the challenge of creating responsive waves and ripples by linking 12 channels of sound to three speakers which the water container – with a diameter of a South African R5.00 coin – straddled. This setup enabled a properly infinite variety of waves and ripples through which light could be projected. Robert became an active co-performer with various musicians and others within the womb-like interior space of Aurora by manipulating the sound inputs into the speakers that cradled the water according to how he felt at each moment. Aurora was also programmed so it could play itself within specific parameters of randomization without Robert necessarily needing to be at the controls.

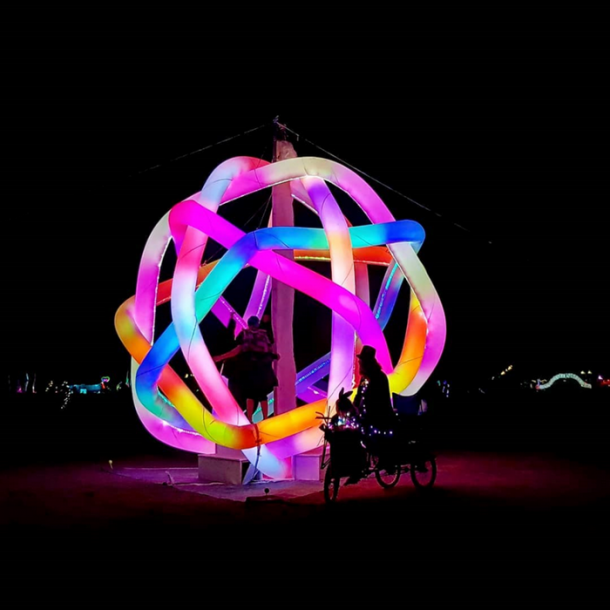

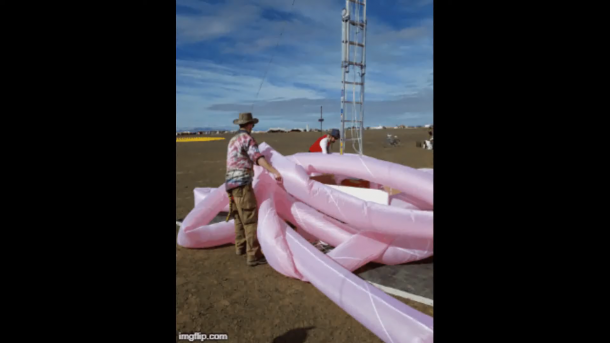

Robert then created Earthstar in 2018. This work is an icosidodecahedron made up of six interwoven and interlocking hollow rings made of inflatable vacuum bag nylon tubes covered in a ripstop nylon sleeve. He relates that for this sleeve he sewed the parachute nylon on the bias, using his grandmother’s sewing machine, for about 90 running meters to make the spiral-walled tube, which was inflated using a high-pressure blower, and then kept inflated using a diaphragm pump hooked to a custom built control gear and a solar panel with battery.

He has explained further that part of his motivation for this work includes to visually, by means of shape and moving light, explore ways in which the rings, pentagons and triangles could be made to both show and hide their symmetrical interrelationships, and thus at least partly reveal or conceal – at any given moment – how frequently the same numbers appear and complement each other.

Earthstar, 2018. 5 meters diameter, multimedia including light emitting diode electronica (Photo: Ginny Lin)

In the 2018 AfrikaBurn WTF Guide (on page 12) he states that Earthstar “is a portal into another dimension”, and exactly which dimension that might be is up to each participant. For Robert, the dimension he is investigating in all his light art works is one of exploring mechanics of light and how to make visible some of the interesting ways in which machines can be programmed to interact with and project light, with an emphasis on otherworldliness and randomisation. He actively seeks out ways in which to tease out personally satisfying inner machine aesthetics – that, for example, an engineer or computer programmer might appreciate – and make those elements plain for everyone to see by means of projected light art.

In the video proposal to AfrikaBurn for Find Yourself, Robert shows various experiments of shining laser light through the rotating glass disc of a lumia wheel which he said “yields something sublime”. When pressed to expand on this he indicated he was aiming for both himself and participants to be transported into feeling a sense of release from being fully in the real world into an emotional experience of something beyond aesthetic bliss.

Furthermore, the sheer complexity of such machines constructed by Robert, usually from scratch, is astounding. For example, the machine that he constructed to peer into the inner workings of water waves and ripples and then project those on to the dome of Aurora so everyone could see the outcomes of such lookings, seems to me to be impossibly complex.

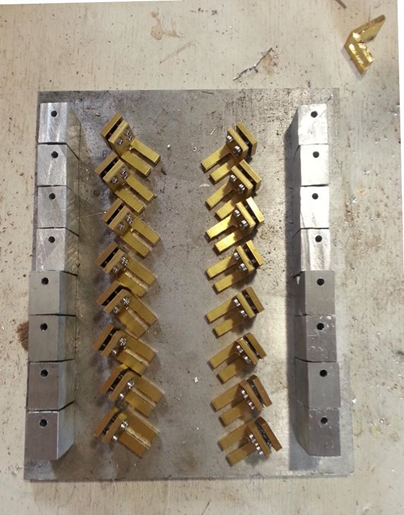

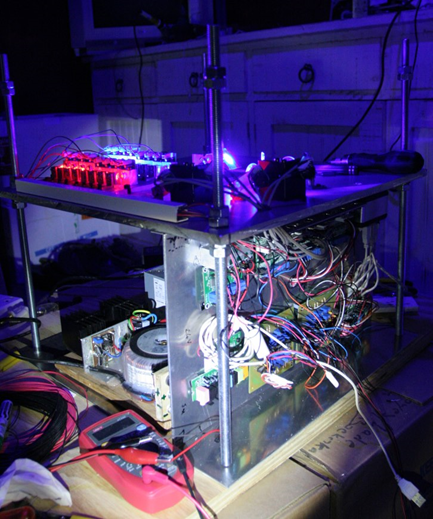

The following two images of Aurora, 2013: some thrillingly complex inner workings, while still under construction. The first image shows the first hand-cut diode blocks and mirror mounts for the red and blue laser arrays. On the right most of the electronics have been loosely placed prior to final testing, after which the light table was dismantled and rebuilt with adjustments to include the green lasers (Photos: Robert van der Vliet).

Robert made many Aurora components from scratch and scrounged others from discarded equipment, gradually fitting parts together and figuring out how best to achieve the original idea as he went along. Such “vertiginous complexity” (Morley 2010: 1) of the inner workings of Aurora, just of itself, can also give rise to “a tension, conflict or incompatibility between imagination and understanding, as in the case of the sublime” (Olivier 2001: 99).

Aurora, 2013. Light table showing how the lasers are amplified then combined to shine upwards (in the centre) then through the water, onto the dome (Photo and annotation: Robert van der Vliet)

Thank you, Robert, for transporting me – and quite possibly many others – into some exquisite realms of the sublime, now re-experienced despite that we have been facing the deep losses and difficulties associated with COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns.

References cited:

Olivier, Bert. 2001. Revisiting the sublime in painting. South African Journal of Art History 15(1): 96-101.

Morley, Simon. 2010. Introduction // The Contemporary Sublime. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.